Introduction

The provinces of British India formed the backbone of colonial administration from the early 17th century until independence in 1947. What began as modest trading posts established by the British East India Company along India’s coasts gradually evolved into powerful presidencies Bombay, Madras, and Bengal. These presidencies became the pillars of governance, commerce, and military control, shaping the colonial state in profound ways. Over time, the system expanded into a complex network of provinces, each reflecting the immense political, economic, and cultural diversity of the subcontinent.

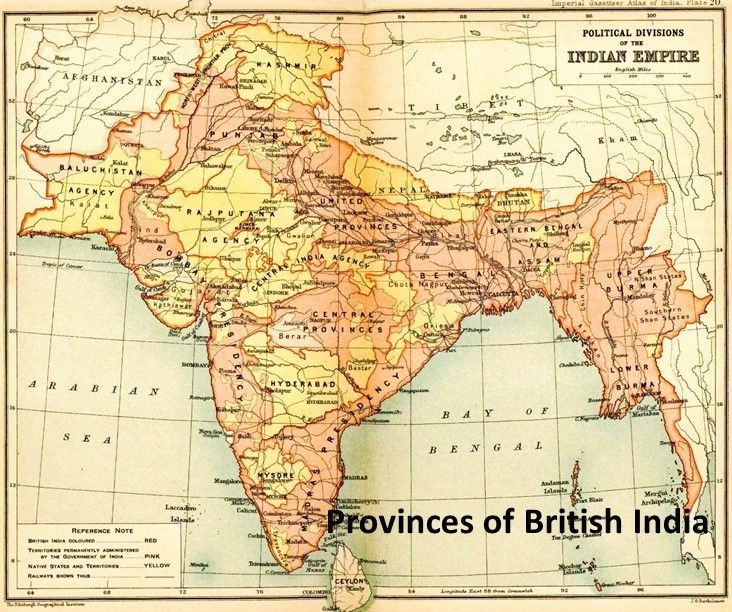

The Revolt of 1857 marked a decisive turning point in this trajectory. With the suppression of the uprising, the British Crown assumed direct authority, ending Company rule. India’s governance was reorganized, and provinces were placed under Governors, Lieutenant Governors, or Chief Commissioners depending on their size and strategic importance. By the late 19th century, eight major provinces Bengal, Bombay, Madras, Burma, Punjab, Assam, the United Provinces, and the Central Provinces and Berar formed the core of British India. Alongside these, smaller provinces such as Ajmer Merwara, Coorg, and the North-West Frontier Province were administered separately, highlighting the layered nature of colonial control.

Evolution of the Provincial System

The Provincial System was dynamic, constantly reshaped to suit British political and administrative needs. Boundaries shifted, provinces were merged or divided, and new units were created to consolidate authority. A notable example was the controversial partition of Bengal in 1905, which created Eastern Bengal and Assam. Though short-lived, lasting only until 1912, it revealed the colonial tendency to reorganize territories for administrative convenience rather than local sentiment. That same year, Bihar and Orissa were carved out as a new province, further demonstrating the fluidity of boundaries.

By the time of independence in 1947, British India consisted of 17 provinces. These included Ajmer Merwara Kekri, Baluchistan, Bihar, Coorg, Orissa, the United Provinces of Agra and Oudh, Andaman and Nicobar Islands, Bombay, Assam, Delhi, North-West Frontier Province, Central Provinces and Berar, Panth Piploda, Sindh, Madras, Punjab, and Bengal. Each province had its own administrative machinery, but all were ultimately subordinated to the overarching authority of the Viceroy and the British Parliament.

Provinces at Independence and Partition

The partition of India in 1947 dramatically reshaped these provinces. Twelve provinces—including Assam, Ajmer Merwara Kekri, Bombay, Bihar, Orissa, Delhi, Madras, and the United Provinces became part of the Indian Union. Three provinces—Sindh, North-West Frontier Province, and Baluchistan joined Pakistan. Punjab and Bengal were divided between the two new dominions, reflecting the deep communal and political divisions of the time.

This division marked the end of the provincial system as it had existed under British rule. With the adoption of the Constitution of India in 1950, provinces were reorganized into states and union territories. Pakistan, meanwhile, renamed East Bengal as East Pakistan in 1956, which later emerged as the independent nation of Bangladesh in 1971. Thus, the colonial provinces laid the foundation for the modern political geography of South Asia.

United Provinces of British India

The United Provinces, originally known as the United Provinces of Agra and Oudh, were among the most significant administrative regions. Formed in 1902 by merging the North-Western Provinces with Oudh, the United Provinces became a hub of political activity, education, and nationalist movements. Cities like Allahabad, Lucknow, and Agra played central roles in the freedom struggle, hosting leaders, institutions, and debates that shaped modern India. The region’s intellectual vibrancy made it a crucible of nationalist thought and reform.

Ajmer Merwara Province

Ajmer Merwara was a small but strategically important province in northwestern India. Surrounded by the princely states of Rajputana, it was directly administered by the British through a Chief Commissioner. Ajmer itself was notable for its cultural significance, particularly the Ajmer Sharif Dargah, which attracted pilgrims from across India.

Annexed in the early 19th century, Ajmer Merwara remained under direct British administration. Its governance was overseen by a succession of Chief Commissioners, including Richard Harte Keatinge (1871–1873), Sir Lewis Pelly (1873–1878), and Hiranand Rupchand Shivdasani (1944–1947). These administrators ensured the smooth functioning of the province until independence, when Ajmer Merwara was merged into Rajasthan.

Central Provinces and Berar

The Central Provinces were created in 1861 by merging Nagpur Province with the Saugor and Nerbudda Territories. In 1903, Berar was added, forming the Central Provinces and Berar. Covering much of present-day Madhya Pradesh and Maharashtra, this province was agriculturally rich and culturally diverse. Nagpur, its capital, became a major administrative and commercial center, known for cotton production and trade. The province exemplified the colonial strategy of consolidating territories to maximize economic output.

Panth Piploda Province

Panth Piploda was one of the smallest provinces of British India, located in present-day Madhya Pradesh. Created in 1942 from territories previously under princely states, it reflected the British tendency to reorganize even minor regions for administrative convenience. Though small, its existence highlights the fragmented and often experimental Nature of Colonial Governance.

Assam Province

Assam became a separate province in 1874, carved out from Bengal. Known for its tea plantations, forests, and ethnic diversity, Assam was crucial to the colonial economy. Initially administered by a Chief Commissioner, it later came under a Governor. Its boundaries shifted over time, especially during the creation of Eastern Bengal and Assam in 1905. After independence, Assam became a state of India, though its territory was later divided to create new states such as Meghalaya, Mizoram, and Nagaland, reflecting its complex demographic and cultural composition.

Nagpur Province

Before its merger into the Central Provinces, Nagpur Province was an important administrative unit. Renowned for cotton production, Nagpur developed into a significant commercial hub under British rule. Its integration into the Central Provinces reflected the colonial strategy of consolidating territories for efficiency and economic gain.

Cultural Dimensions of the Provinces

Beyond administration, the provinces of British India were centers of cultural activity. Regions like Karnataka, which fell under the Madras Presidency, retained their rich traditions of dance, folk art, and music. Bharatanatyam, Yakshagana, and other art forms flourished despite colonial dominance, reflecting the resilience of Indian culture. Similarly, Punjab and Bengal nurtured literary and artistic movements that intertwined with nationalist aspirations, producing poets, writers, and reformers who challenged colonial authority and inspired mass movements.

Conclusion

The provinces of British India were more than administrative divisions; they were the framework through which colonial power was exercised and Indian society was reshaped. From large presidencies like Bengal and Bombay to smaller provinces like Ajmer Merwara and Panth Piploda, each played a role in the political, economic, and cultural history of the subcontinent. Their legacy continued even after independence, as many provinces formed the basis of modern Indian states. The transformation from provinces to states marked the end of colonial structures and the beginning of a new democratic era for South Asia.