Introduction

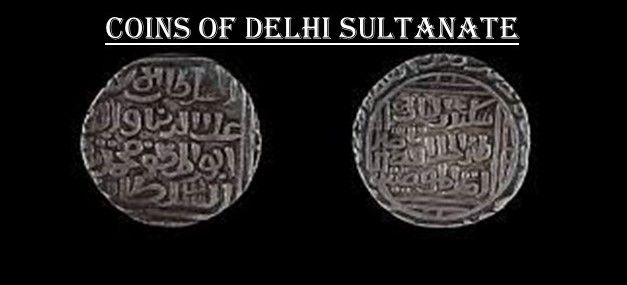

The Delhi Sultanate (1206–1526 CE) marked a pivotal moment in Indian monetary history. By the 14th century, the Sultanate had introduced a structured monetary economy that reshaped trade, taxation, and social life. Coins issued during this period were not merely instruments of commerce; they were Powerful Symbols of Sovereignty, religion, and artistic expression. Each ruling dynasty contributed to the evolution of coinage, leaving behind a rich numismatic legacy that reflected both political authority and cultural synthesis.

Early Coinage: Muhammad Ghori and the Slave Dynasty

The foundations of Sultanate coinage were laid by Muhammad Ghori (Muhammad bin Sam). After consolidating power in India, he issued billon coins of the “bull-horseman” type, featuring a bull on one side and a horseman on the other, with Nagari inscriptions such as Sri Mahamad Sam. Ghori also minted gold coins imitating local designs, placing the seated goddess Lakshmi on the obverse and inscribing his name in Nagari script. His general, Bakhtiyar Khilji, struck coins in his master’s name, often depicting a charging Turk horseman. Copper coins were also introduced, though silver coinage was absent in Ghori’s Indian dominions.

After Ghori’s death, his general Qutbuddin Aibak, founder of the Mamluk (Slave) dynasty, did not issue coins in his own name. His successor, Iltutmish, however, transformed Sultanate coinage. He introduced silver coins bearing the Kalimaand the name of the Abbasid Khalifa, al-Mustansir, symbolizing his investiture in 1228 CE. These coins established the “tankah” standard, which became the basis of currency for centuries.

Khilji Innovations

The Khilji dynasty expanded coinage significantly. Alauddin Khiljiissued abundant gold and silver tankahs, introducing at least fourteen denominations in both round and square shapes. His coins were heavy and standardized, reflecting his economic reforms. Copper and billon coins were also minted, with denominations such as visua (one-twentieth of a gani) and paika (one-fourth of a gani). Many coins bore mint names, ensuring accountability and uniformity across the empire.

Tughlaq Experiments

The Tughlaq dynasty followed Khilji patterns but introduced bold innovations. Ghiyasuddin Tughlaq experimented with new designs, while his successor Muhammad bin Tughlaqbecame famous for ambitious numismatic experiments. He issued coins from multiple mints across India, reintroduced the Kalima, and produced coins in varying weights and metals. His attempts to standardize currency across Delhi and Daulatabad led to at least 25 variations of billon coins and 12 types of copper coins. Though visionary, these experiments often caused confusion in trade.

Firoz Shah Tughlaq later inscribed the names of Abbasid Khalifas on his coins, reinforcing religious legitimacy. His coins bore titles such as Saif amir-ul-momnin abul-al-muzaffar, linking political authority with Islamic faith.

Lodi Coinage and Sher Shah’s Reform

The Lodi dynasty continued issuing billon and copper coins, typically inscribed with formulas like al-mutwakkal ali and mint names such as Delhi. Their coinage reflected continuity rather than innovation.

The Afghan ruler Sher Shah Suri, who briefly interrupted Mughal rule, introduced significant reforms. He eliminated billon coinage, issuing only silver and copper coins. His silver rupiyabecame the prototype of the modern rupee. Sher Shah’s coins bore the Kalima, names of the four Khalifas, and his own name in both Arabic and Nagari scripts, symbolizing cultural synthesis and administrative efficiency.

Cultural Significance of Sultanate Coins

Coins of the Delhi Sultanate were more than currency; they were political statements and cultural artifacts. The inscriptions in Arabic and Nagari reflected the blending of Islamic and Indian traditions. The use of religious symbols, Khalifa names, and royal titles reinforced legitimacy. The evolution of coinage mirrored the Sultanate’s administrative sophistication and its integration into global trade networks.

Conclusion

The coinage of the Delhi Sultanate represents a new era in Indian monetary history, combining local traditions with Islamic influences. From Muhammad Ghori’s bull-horseman coins to Sher Shah’s standardized silver rupiya, the Sultanate Coins Reveal the Political Ambitions, religious affiliations, and economic strategies of its rulers. These coins not only facilitated commerce but also served as enduring symbols of authority and culture, shaping the legacy of medieval India’s economy.